|

|

|

|---|

THE ROTTEN KID OUT OF LA JOLLA

ACCORDING TO HARRY ANSLINGER'S GORE FILE:

Name: - Donald S. Crosby, (age 16) / Mrs. Ida C. Mackeown (Victim) - Location: - La Jolla Ca. Date: - Dec 16, 1952

What the Narc’s were claiming

La Jolla, California - Male 16 Paroled juvenile delinquent, under influence smoking marihuana, murdered Mrs. I. KacKeown, 67, grandmother, inflicting 35 knife wounds. She called him marihuana user and threatened to call police. -- Article by James C. Munch; "UN Bulletin on Narcotics"-1966 Issue 2

Juvenile delinquent on parole, murdered 67-year old grandmother with 35 stab wounds, while under influence of marijuana. -- The Truth about Marijuana - STEPPING STONE to DESTRUCTION June 1967

? - D. Crosby, - La Jolla, Calif. - M - 16 - Paroled juvenile delinquent, under influence smoking marihuana, murdered Mrs. I. MacKeown, 67, grandmother, inflicting 35 knife wounds; she called him marihuana user and threatened to call police. Arrested -- 6th conference report - INEOA 1965

NEWSPAPER ACCOUNTS:

Los Angles Times

[**]- Dec. 16, 1952 pp 2 "Woman Artist Found Knifed to Death in La Jolla Home"

[**]- Dec 17, 1952 pp 2 "Blames Marijuana - Youth Tells How He Killed Artist"

[**]- Dec. 19, 1952 pp 26 "Murder Hearing Set in La Jolla Slaying"

Redlands Daily Facts - Redlands, California

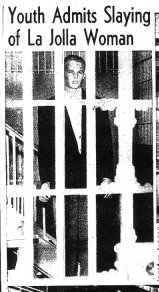

[S-Dec 1, 1952 ] “16-Year-Old Youth Admits Killing San Diego Artist”

[S-Dec 17, 1952 ] “Youth Says He Was Doped When He Killed Artist”

[S-Mar 27, 1953 pg. 1] “Boy, 16, May Get Life For Stabbing”

[Key-finder - Case #6]

A ROTTEN KID ; MUSEUM COMMENT

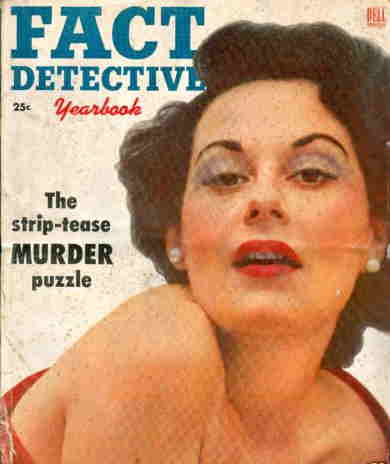

It has been our experience that any facts, or for that matter anything you read in a “True Detective” genre magazine article should be viewed with great suspicion. Whatever else can be said about this genre, truth and accuracy is not one of them. Thus (obviously) the reader should approach this article with great suspicion but for now it seems to have the best description of events we have out there.

AS PER FACT DETECTIVE Yearbook – 1953, pg25

“The Kid Smoked Reefers" ; But Was he really Gone On The Weed When He Invaded The Painter’s Studio?

WARNING: Some transcriber errors are possible:

IN EARLY NOVEMBER of 1952, a teacher in San Diego's Hoover High School caught three junior students smoking marijuana cigarettes in the boys' locker room. The school authorities began a quiet investigation which revealed that the reefer habit was alarmingly widespread among the city's teenagers.

At the next PTA meeting, it was discovered that many of the parents, already had some inkling of the burgeoning menace which threatened their children. They were aware of frightening words which had filtered into the already weird argot of the post-war generation. The kids still "dug" bop talk, but now there were references to “tea," ''bombers,:' "sticks," and "blasting off." They referred to one another as "gone goslings" and "ride men." The "chicks" and "gates" regularly got together at beach parties off Seal Rock and Del Mar to get "high" on the weed. They came back enervated and washed out in the grip of a powerful depressant which affected them like a wine jag. Yet their parents could smell no liquor on their breaths. It was evidently a new kind of binge ---much worse than any induced by alcohol.

The parents were told that the marijuana traffic in the San Diego area was at its all-time high. Youngsters as well as adults had been arrested who made a lucrative business of peddling the weed in school areas.

The authorities admitted that southern California seemed made to order for the "tea trade." Hollywood already had its share of reefer scandals involving stars and other, motion picture luminaries. Only a few miles to the south was the Mexican border. The hot rod set could tear down to Tijuana or Agua Caliente and buy all the sticks they could pay for. It was easy too, for the organized tea pushers to make smuggling trips north.

A petition was drawn up that night at the PTA meeting, It called up District Attorney Don Keller to clean up the situation and to use every facility at his command to Crack down on the peddlers and the ring leaders behind them.

THE ROTTEN KID HIMSELF

THE ROTTEN KID HIMSELFThe newspapers cooperated in collateral campaign, and took it upon themselves to familiarize their readers with the facts. They published photographs of impounded reefers and described the clinical effects upon the users.

By the middle of December more than l2,000 persons in San Diego and its suburbs had fixed their names to the petition. One of these signers was a 67- year-old artist, the nationally known miniature painter, Ida Mackeown, who lived in the suburb of La Jolla. The newspaper stories made a deep and abiding impression upon her. She was shocked by the accounts of what was happening to the younger generation,

A little knowledge is a dangerous thing. Miss Mackeown had actually never seen a reefer. Her idea of what one looked like was formed from what she read in the papers. She learned that there were two types of “joy sticks.” One thin and small, and a larger size known as a “bomber.” They closely resembled ordinary cigarettes which Miss Mackeown herself did not smoke. The artist, in fact, knew very little about cigarettes keeping none in the house and discouraging their use by her infrequent visitors. This circumstance trivial as it seems was to have fateful consequences.

IDA MACKEOWN was something of a character. She lived alone in a picturesque gray stucco house at 1271 Virginia Way. Perched high on rugged cliffs, it was an ideal home for an artist. Below stretched the sun-dappled cobalt of the Pacific, seething into lacey foam between the rocks. Each sunset was a molten crucible of inspiration a challenge to a painter. The nights were tranquil, murmurous with the breathing of the sea.

Miss Mackeown kept no servants, but her three pets and her work left her far from lonely. A chattering parakeet whose case was never closed had the run of her studio, where its brilliant colors vied with those of Ida’s palette.

Smokey a soot-black cat, would stare with unwinking eyes while the artist worked over the miniatures which had brought her fame. Fritzie, the white toy poodle, would beg for handouts of cookies during tea-time.

THE ROTTEN KID'S VICTIM

THE ROTTEN KID'S VICTIMOnce a week, a hired girl would go through the house, dusting, scrubbing, and changing the linen on the bed. Every week, a gardener would mow the lawns, clip the hedges, and spade the turf border of the cosmos bed. Actually, there was no regular gardener. Itinerant nurserymen and neighborhood youngsters made the rounds of the houses along Virginia way. Miss Mackeown always found someone to work for an afternoon when the grounds needed attention.

On Saturday, December 13, she was busy in her studio near the back of the house. Swelling notes of a Brahms concerto surged from her radio. Working from a child’s photograph, her painting took shape beneath the large magnifier on its gooseneck stand. She held three pin-point sable brushes ready between the fingers of her left hand while she worked with a fourth. She was so preoccupied that she didn’t hear the soft footfalls behind her. She had no idea of the intruder’s presence until Fritzie, the poodle, began to bark. She turned and surveyed the boy in surprise.

"What are you doing here? ” she demanded.

"I rang the bell," the boy mumbled.

"I guess you didn't hear me."

The woman sat waiting for him to explain. "Well? Speak up. What do you want?"

The kid seemed flustered. He wet his lips. "Did you happen to find a cigarette lighter?" he asked. "I must have left it here last time I was here."

Ida Mackeown was somewhat annoyed at this bumbling youth. She had a highly developed sense of personal' privacy, and she did not like the way he had barged into her studio. Besides, as she gazed at him, it struck her that there was something wary and tense about him. He looked guilty, somehow.

SOME GUY LOOKING IN A TRASH CAN, HOLDING THE ROTTEN KID'S KNIFE

SOME GUY LOOKING IN A TRASH CAN, HOLDING THE ROTTEN KID'S KNIFE"I haven't found it," she said a little sharply. "You weren't inside the house, so it wouldn't be here, would' it?

"I guess not," he muttered, fumbling in his pocket for a pack of cigarettes. One of them fell to the floor. Miss Mackeown stared at it

It was one of those extra-long cigarettes, and her quick mind immediately reverted to what she had read in the papers about high-school youngsters smoking marijuana. Some of those reefers, she, recalled, were of extra-large size and were known as “bombers.”

Actually, the cigarette on the floor was an innocent Pall Mall, but', she leaped to a conclusion. So that was why this strapping youth acted so peculiarly!

"Young man," she' snapped, “have you been smoking marijuana?"

The expression on his pale face changed from one of confusion to sudden menace. "It ain't so!" he growled taking a step toward her.

Miss Mackeown leaped to her feet in fear. "Get out!" she shrilled backing away. "Get out!."

But he kept coming. She uttered a feeble scream of terror, and then he was on her, twice her size. There was a series of gasping, inarticulate sounds. The poodle took fearful flight into a bedroom. The parakeet squawked excitedly on its perch. On the radio, a Beethoven sonata had just come to its end.

"This program has come to you,” the announcer intoned, "through the courtesy of the Majestic Company, dealers in the highest quality products . . . "

IDA MACKEOWN'S studio radio was still playing on Monday morning when 14-year-old Francey Smith rang the doorbell at 8 o'clock. Francey lived across the street. Her father and mother, Dr. and Mrs. Francis Smith, were friends, of the artist as well as neighbors. The Smiths' regularly took the San Diego newspaper. Miss Mackeown subscribed to the Los Angeles paper. It was their custom to swap the Sunday editions on Monday morning.

Francey pressed on the bell push again. From inside came the poodle's frantic yapping. Miss Mackeown did not come to the door.

The girl waited a minute more, then returned to her home.

“Maybe she's still asleep." Mrs. Smith remarked.

Francey sat down at the breakfast table and began to butter her toast. “Not with the racket Fritzie’s making," she said. “Anyway, Sunday's paper and the one for today are still on the porch”

Dr: Smith set down his coffee cup, "That's odd," he mused. “And you say the radio's playing?"

“Loud, too."

The doctor looked at his wife. His eyes were disturbed.

"Maybe you'd better call her up, hon," he said. “See if you can get her on ,the phone,"

Miss Mackeown did not answer her telephone. The Smiths were now definitely worried. Their neighbor, after all, was well advanced in years. Perhaps she was ill and unable to contact anyone. Right after breakfast, the Smiths sent Francy across the street once more. There was still no response in the gray stucco house.

At 9 o'clock, Mrs. Smith herself went to the home of her neighbor. The newspapers were on the porch, as her daughter had said. Moreover, the front door was not properly latched, a space showing between the jamb and the edge of the door. Mrs. Smith rang the bell, long and hard. Then she pushed open the door and stepped into the dimly lit hall where she was greeted excitedly by the whining poodle.

"Ida?" Mrs. Smith's questioning voice tentatively.

There was no answer.

The doctor’s wife walked toward the studio where the radio was blaring raucously. The room was splashed with sunlight. On the bookcase hopped the parakeet, chattering, wildly. Ida Mackeown was a huddled heap on the floor.

She sprawled face down, her orange smock stained with blood.

Mrs. Smith ran back for her husband. The doctor took one look at the welter of stab marks on the woman's face and saw that she was dead. He called the police.

The three detectives who raced to La Jolla from San Diego police headquarters were all struck by the same thought as they looked down at the murdered woman. The wounds on her face, her chest, and abdomen seemed to form a deliberate pattern. It was as if the killer had slashed his victim according to some ritualistic plan.

“About 25 stab wounds,” deputy" Coroner Jess Canale estimated. "Eight in the breast, ten in the face, and the rest around the body. Look for a broad-bladed knife--something like a bayonet.”

Detective Lieutenant Mort Geer and Sergeants Anthony J. Maguire and Paul C. Walk went through the house. They found other clues, but not the broad bladed death weapon. There were bloodstained towels in the bathroom, and a red smudge on the bathroom door jamb which might have been a fingerprint. The killer had cleaned up in the wash bowl before leaving.

He had also wiped the blade of his knife free of blood. The cops found a kitchen towel which he had used for this purpose.

There was one more clue, discovered when the body was moved to the morgue ambulance. A Pall Mall cigarette, unsmoked and. Blood stained, was found on the floor where Ida Mackeown had lain.

There were no other cigarettes in the house. Dr. and Mrs. Smith told the' Officers that Ida never smoked. The Pall Mall, then, must have been left by the slasher.

WHILE POLICE technicians set up shop in the studio and a squad of legmen began a round of doorbell-ringing in the neighborhood, the Smiths filled in the detectives on the dead woman's background, .

Ida· Mackeown, originally from New York, was a divorcee. She had Come out in New York society during the 1903 season, and her charm and patrician beauty made her one of the most glamorous debutantes of the day. Shortly afterward she married Valentine Koch, handsome and wealthy. A daughter was born to the couple. The marriage didn't last, and in 1912 at the age of 27, Ida secured divorce. She turned to art to fill the void in her life, and revealed a surprising talent which was acclaimed by the critics. Her miniatures were in great demand, some of them selling for as much as $1,000 apiece.

In 1940, Ida moved to the West Coast. Her daughter, married now was in Hawaii with her husband, Marine Corps officer. The artist settled down in the tasteful stucco house overlooking the Pacific. Although well-to-do in her own right, Ida lived in comparative austerity, having the true artist's simple tastes. She rose each morning at 6 and put in a full day's work in her studio.

According to the Smiths, her friends were few, most of them persons with an interest in either art or drama. She had two cousins who lived in nearby Pacific Beach.

Nothing the officers learned about Ida Mackeown's life appeared to hold a clue to the secret of her death. The sadistic mutilation of the body seemed to point to a killer with pathological tendencies. At police headquarters in San Diego, Captain Graham Roland, chief of detectives, circulated a bulletin over the statewide police teletype system. Enforcement agencies throughout California were warned to be on lookout for a knife wielder who might still be wearing bloodstained clothes. He alerted the Mexican border patrol and, closer to home, initiated a wholesale roundup of known sex offenders in the San Diego area. He then joined Lieutenant Geer in La Jolla, to take charge of the investigation there.

"We figure the murder must have taken place sometime Saturday afternoon," the lieutenant told him. “Mr. Allison next door saw her take the dog out at about 11 o’clock. The Sunday paper is still outside on the front stoop, so that should put the crime between Saturday noon and Sunday morning. There were no lights burning in the house when the body was found. That makes it look like a daylight' job."

This analysis jibed with the preliminary autopsy report. Coroner A. E. Gallagher phoned in to tell Roland that death had occurred some 24 to 36 hours before discovery of the corpse.

"What about the weapon?", Roland asked him.

"A long knife with a blade two inches Wide. We'll know more about that later.”

"How about a sex angle?"

"No evidence of that, Captain. More than that, I can't tell you. Your guess is as good as mine."

A search of the house and grounds had not turned up the death weapon. Roland sent out a detail to scour the rest of the neighborhood.

Mrs. Dalsy Richards and Mrs. Mary Kendrick, the dead woman's cousins from Pacific Beach, reached the Mackeown home shortly after noon. The Smiths had notified them of the tragedy.

Stunned by what had happened, the two ladies could think of nothing which would help the police. Mrs. Richards had visited with Ida as recently as Thursday. The artist had been in her customary good humor and discussed a trip she intended to make to Hawaii to visit her daughter.

“She even talked about the possibility of selling the house and settling in Hawaii for good,” Mrs. Richards said tearfully. “She certainly didn’t act like anything unpleasant was troubling her.”

The two women toured the five-room house with the investigator. The two women toured the five-room house with the investigators. They found nothing out of place. Ida’s jewelry was intact in a strong box hidden in her dresser drawer. There was even a small amount of cash in a purse on the bureau top. She rarely kept any large sums, the cousins said, paying most of her bills by check.

Miss. Mackeown’s checkbook was found in a Sheraton secretary in the studio, and the stubs showed no unusual expenditures.

Learning that the artist owned an apartment house and several other pieces of property in Pacific Beach, the cops contacted the San Diego real estate agency which handled her business affairs, but discovered nothing helpful.

THE FIRST BREAK came from the detail which was combing the neighborhood. Sergeant Walk brought back with him a crudely-made trench knife. “Found it in a trash can up the street,” he announced. “I think it’s what we’ve looking for.”

Roland examined the knife, which was obviously hand-made. The blade, a broad file, ground and honed to razor sharpness, was set into a curved handle of poured aluminum.

Although no traces of blood showed on the knife, the dimensions conformed with what was known of the murder weapon.

"An awful lot of care went into the making of this .knife," Lieutenant Geel' declared. "Its owner must have had a pretty special reason for getting rid of it.

Walk told his superiors that' he had shown the knife around at the houses in the immediate area of the trash can, but that no one recognized it.

Crude though it was, the knife had evidently been made by someone with access to equipment not ordinarily found in the home. Intense heat had been required to mold the aluminum. Also a carborundum grinder must have been used to whet the tile to its present sharpness. It looked like the owner had spent some time in a metal shop, although he was not quite a professional craftsman.

“Maybe some school kid made it during vocational training,” Roland guessed. “It’s just the kind of thing a kid would work on.”

The next lead came from a woman who had noticed just such a boy on the Mackeown porch at 1 o’clock on Saturday afternoon.

“I was on my way to do the marketing,” she told Sergeant Manuire, when he reached her house in the course of canvassing the neighborhood. “I saw this boy go up the walk and ring the bell. He was a tall boy, now that I remember it. He had blond hair and wore one of those white T-shirts.”

“Did you see Mrs. Mackeown open the door?”

“No, sir, I didn’t. I was in a hurry and I just kept on walking.”

She said she hadn’t recognized the youth as any of the neighborhood boys, but that he looked like any of a number of young men who came to Virginia Way looking for yard work or odd jobs

The yard work angle was the hottest lead to turn up thus far, when Maguire reported back to Roland. The Mackeown grounds were neat and well kept, the grass having been cut within the past few days, and the flower bed near the garage freshly weeded. The captain questioned the Smiths and learned that the artist was in the habit of hiring itinerant gardeners to work on her place. Most of the residents along Virginia Way did the same thing. Within a few minutes, the cops were able to learn the names of five such youngsters who did yard work in the neighborhood.

Walk and Maguire set out at once to round up these boys. They had a little more to work with than the housewife's sketchy description. It was probable that the youth, were he the killer, smoked Pall Mall cigarettes. It was also probable that he was known to carry the home-made knife. Too, he likely had access to a metal shop where the- knife had been made.

This sequence became more than mere supposition when the crime lab reported finding microscopic traces of blood on the hand-crafted knife. That it was definitely the murder weapon became a certainty when tests at the morgue revealed that the blade fitted the stab wounds in the elderly artist's body.

A process of elimination quickly narrowed down the list of five boys. Three of them were dark-haired, and no way fitted the suspect seen on Ida Mackeown's porch. Of these three, one admitted having formerly worked on painter’s grounds, but proved an airtight alibi for the Saturday in question. The other two claimed to have no knowledge of Miss Mackeown whatever.

The two remaining yardmen were blonds. Both had worked from time to time on the artist’s grounds. One of them, 16-year-old Donald Crosby, actually admitted having mowed Mrs. Mackeown lawn on Thursday. “Why would I want to go back there two days later?" he asked reasonably. “That place wouldn't be ready for another manicure for a week.”

“Okay, Don,” Walk said “that makes sense. Tell us what you did on Saturday. Start from the time you got up in the morning.”

CROSBY REVIEWED his day, saying he had awakened early and, after breakfast, driven down to his father’s nursery. He worked for an hour in the greenhouse and then went to La Jolla to take care of two gardening jobs for which he had contracted the week before. After lunch, he visited his girl friend and the two had driven in her car back to his father’s place.

“Where were you at 1 o’clock?" Maguire asked.

Crosby thought for a second. “The chick and I must have been over at Dad’s about that time. Then we put some gas in the car and drove around for the rest of the afternoon.”

Walk tapped his pocket as if looking for a cigarette. Maguire shook his head. “Don’t look at me,’ he said. “I just smoked my last butt. Maybe the kid’s got one.”

“Sure,” Don said. He pulled a red pack out of his dungarees and offered a Pall Mall to Sergeant Walk.

The two cops pulled the same trick, moments later, on 18-year-old Steve Kusuosco, the fifth boy to be questioned. The ruse produced the same results. Steve also smoked Pall Malls. Unlike Don Crosby" however, the tall tow-headed Hoover High School senior, had very little to offer in the way of an alibi.

"When was the last time you saw Mrs. Mackeown?” Walk asked him.

The part-time gardener had difficulty remembering. "Must have been more than a couple of months back," he said. "I’ve had a lot of bad luck at her place. Somebody always beats me to it. I guess I haven't been hitting it the right time."

“Did you try on Saturday?"

“I passed on Saturday, but the lawn looked pretty good to me, so I decided to give it the go-by.

Steve was unable to account satisfactorily for his movements at 1 o'clock. He claimed he had left La Jolla for home at about 12. He admitted that his folks were out when he got there, and that he had no way to prove the time of his actual arrival.

The officers now had two likely suspects although there was a good chance that the killer was neither of them. Both of the youths were students at Hoover High School, and had access to the school’s vocational metal-working shop. Both: smoked Pall Mall cigarettes. Both knew Ida Mackeown and had worked occasionally on her Virginia Way property.

Pen Crosby’s father partly confirmed the boy's alibi. He recalled that Don and his 15-year-old girl friend had dropped in at the nursery sometime between half-past 12 and 1:30on Saturday afternoon. The elder Crosby had presented Dan’s companion with a camellia, and spent a few minutes chatting with, the youngsters. They: then drove off.

Kusuosco's parents had taken the family car and gone, on Saturday morning, to the supermarket on their weekly shopping expedition. They had been away from home until after 2 o'clock. They found Steve in the house when they returned.

The next development came from headquarters. Fingerprint men working over the latent smudge etched in blood' on Mrs. Mackeown's bathroom door, had succeeded in raising a partial print.

They admitted that the print had insufficient points of identity for classification purposes. Nine of these were needed to stand up as evidence in court, and the technicians had obtained only five.

“Just find us the guy,” they told Lieutenant Geer. “We've got enough to tell You whether he left that smudge on the bathroom door. Whether it stands up in court or not depends on how far you can carry the ball."

A QUICK CHECK of the criminal identification files showed nothing on Steve Kusuosco. However, in the juvenile section, the officers found a card on Don Crosby.

The good-looking blond kid had been in a jam at the age of 14. He had broken into some cabins at Culzura and made off with several rifles and some other loot. An alarm was turned in and the boy took to the woods. He was tracked by a deputy sheriff to a stand of high ground and, when called to surrender, the kid had played tough. From behind the rocks, he let go a fusillade. It was later learned that he had not actually aimed at officers, but was firing low in an effort to intimidate them.

For this caper in 1950 young Crosby was turned over to the California Youth Authority and sent to the Fred C. Nelles State School at Whittier. Here he served the better part of a year until his parole in 1951. There was no record of further trouble after this escapade.

California state law forbids the fingerprinting of juveniles, so Don’s prints were not on record. Walk and Maguire drove to his home to pick him up. On the way back they stopped off for Steve Kusuosco.

“What’s the big idea?” Kusupsco wanted to know.

“We just wanted to take a look at your prints. Of course you can refuse if you-want to,” Walk said. “That’s, of course; if you've., got anything to hide."

I got nothing to hide," Kusuosco said. "Maybe that'll put a stop to this nonsense once and for all.

"That's the way to look it," Maguire agreed heartily. “Put yourself in the clear, and we won’t trouble you any further. Isn’t that right, Don?”

“Sure,” Crosby said. “Take all the prints you want.”

At headquarters; the fingerprint men inked the boys fingers and took their samples. They then retired to the crime lab. They returned shortly and whispered to Lieutenant Geer.

Geer nodded, his face inscrutable, and walked over to the boys.

"All right, Steve;" he said. "Take off You're free to go home.”

Don Crosby bunched forward in his chair.

"How about me?”

Geer rubbed his chin. "Yeah," he said. "About you, now. You know we got a print off Miss Mackeown's door.

We just identified it."

Crosby ran his fingers through his thick hair. Despite his six-feet-two, he looked exactly what he was --- a frightened school kid.

“Let me tell you something,” blurted. "I didn't give you the whole truth before. I was at Miss Mackeown on Saturday. But don't get me wrong," he added hastily. “l didn't kill her."

“All. right, Don," Geer said softly. "What's the rest of it? Just what did happen on Saturday?"

"Like I told you, I did a couple of yard jobs in La Jolla. On the way back, I stopped off at her house."

"Why? You were just there the Thursday before."

The kid began to sweat. “Sure" he said. "Sure. I didn't touch the hedges when I was there on Thursday. I figured maybe she’d give me a buck if I trimmed them."

“What happened?”

"I rang the bell. I guess that's how my print got on the door, Miss Mackeown showed, but she said nothing doing. She'd wait till the next time."

“And you didn’t go inside?”

“No, sir.”

“Well, son,” Geer said, "let me tell you something. I didn't tell you the whole truth before. We found that print on a door, all right. Only it was on the bathroom door, inside the house. And the print was in blood, son,”

CROSBY LIT one of his Pall Malls and began to drag on it nervously. Into the room filed Captain Roland and Police Chief A. E. Jansen. They drew up chairs around the wilting youth. A uniformed attendant brought in a tape recorder and set it up. Roland took one of the mikes and handed the other to the boy.

Don stubbed out his butt. “No use trying to kid you any more," he said. "I’m the guy you want." He looked at the still-smoking cigarette in the littered tray.

''Would you' believe it?” he asked.

''It all happened on account of one of them things.”

He then related the extraordinary events which had culminated in the elderly artist’s murder.

Don was a marijuana smoker, he told the cops. On Saturday morning, while working on his jobs, he had consumed eight dollars' worth of tea bombers, the king-size marijuana cigarettes which were being currently peddled for a dollar and a quarter each. As Don himself put it, he was a "real gone kid.”

High from the effects of the weed, and wanting money for more, he recalled that when he had last been at Miss Mackeown’s home he had noticed festoons of Hawaiian leis hanging from a nail in the garage. The boy figured, that if he could manage to steal them," " he could sell them in some downtown' hock shop for 50 cents apiece.

While he mulled over how to get them, he smoked his last bomber and then set out for the house on Virginia Way. First of all, he needed the garage key. That, he knew, must be in the house. He rang the bell and even pounded on the door several times. The radio was playing and Miss Mackeown, working at the back of the house, evidently didn't hear him. The door was unlocked, so he walked in, making his way directly to the studio.

Confronted by the artist, the boy mumbled that he was looking for his cigarette lighter which he thought he had dropped on Thursday, perhaps in the garage, where the garden tools were kept. While talking, the boy fumbled in his pocket for his cigarettes. One of his Pall Malls fell to the floor.

This cigarette, innocent though it was, had precipitated Miss Mackeown 's death.

"The old dame thought it was a bomber!" Crosby said incredulously.

"She'd been reading about reefers in the papers.” She caught me flat-footed. I didn't know what to tell her. Here I was high on the stuff and she starts talking about calling a doctor and the cops. And me with my record!"

Crosby related that as the woman made a move to the door, he slapped her. She began to scream. In order to shut her up, he put his hand over her mouth. Surprisingly strong, she began to wrench herself free. The boy pulled out his knife and first hit her on the head with the handle, then plunged the blade repeatedly into her body until she fell to the floor.

“I hoped she was dead, Crosby said. "I didn't want her to live to identify me."

The storm of blood-letting over, the boy felt a growing wave of nausea. He found the bathroom and was sick. Then he noticed that his dungarees were covered with blood. He washed them in the sink and hung them up to dry. While waiting, he went to the kitchen and cleaned off his knife. Always he avoided looking at the woman he had killed. Finally an hour after the crime, he made his way out of the house, discarding his knife in the trash can a block away on Virginia Way.

Driving to a cabin owned by his father, Don changed his dungarees for fresh slacks and picked up his girl. They visited his father and then drove around for the rest of the afternoon.

"Nearly all the school kids blast," Crosby told the cops. "It makes you feel good, I’ve been doin' it for over a year."

Spurred by the publication of Don Crosby's aroused citizenry rushed the marijuana control petition on to District Attorney Keller for immediate action. For Ida Mackeown, whose name appeared on that petition, it was too late. Ironically---if Crosby's story was true---she herself had died a victim of marijuana.

Don Crosby was arraigned on December 16 before Municipal Judge William Smith who turned him over to the juvenile court, where Superior Judge Robert B. Burch on January 5, 1953, ruled that the prisoner he turned over to the criminal division to be tried as an "adult.

When Donald Crosby went on trial in San Diego superior court, the jury had a difficult question to decide. Was Crosby to blame, or had marijuana so addled his brain that he did not know what he was doing? The jurors heard the evidence and decided against the contention that the big blond kid had not known right from wrong. On March 26 they found him guilty of first degree murder, and Judge L. N. Turrentine pronounced the mandatory sentence of life imprisonment. Only the fact that he was still a minor saved him from the gas chamber.

Crosby comes into a $15,000 inheritance when he is 21, but it is unlikely that he will enjoy it that soon for he will not be eligible to apply for parole for seven years.

EDITOR’s NOTE: The name Steve Kusucsco, as used in this narrative, is fictitious.

MUSEUM CONCLUSIONS:

OK, we all know that Marihuana “The Killer Drug” simply doesn’t have those kind of effects. Were it so, then half the population of California would have killed the other half long ago. HOWEVER, take note the date “1952”, meaning that this case took place right in the middle of the Reefer Madness Hysteria campaign. The very title of the magazine article, “The Kid Smoked Reefers” is a dead giveaway to that effect.

But also note the subtitle, “But Was he really Gone On The Weed When He Invaded The Painter’s Studio”? Meaning that there was a real question over whether the kid (who confessed) to the murder, really had made use of Marihuana OR whether his lawyers were simply using it as a defense tactic to get him out of jail?

This museum has not really spent enough time investigating the details of this case, however the following is known:

HOWEVER from the evidence as stated (and remember, we have not really done a complete investigation), it is our feeling that the kid's lawyer (who knew there was no other out) simply adviced the kid to use the Marihuana Defense angle to get him out of jail.

|

|

BACK ANSLINGER'S GORE FILE |

|---|

WANT TO KNOW MORE:

=====================

Due to space / download time considerations, only selected materials are displayed. If you would like to obtain more information, feel free to contact the museum. All our material is available (at cost) on CD-Rom format.

CONTACT PAGE

|

CALIFORNIA REEFER MADNESS  BACK TO MAIN INDEX |